A musical research and its mathematical echoes: Heterophony

(Instruments of Algebraic Geometry, Bucharest,

20 September 2017 [1])

Franćois

Nicolas, composer

(translation by Matthew Lorenzon)

You kindly offer me the possibility of speaking about music before a public of researchers in mathematics. I would like to take this opportunity to speak to you about a musical research.

I would like to take this opportunity

to clarify two things:

- The

specifics of musical research, in particular in relation to mathematical

research.

- How

a specific musical research - which I lead on the notion of heterophony (you can, next Sunday, come

and hear my Ricercare hétérophonique [2],

which implements this concept) - is likely to resonate on the mathematical

side.

Researches

This research begins with the hypothesis

that, actually, there is such a thing as musical research.

Here, I understand the word research in a strong sense: it does not

mean the basic research for a musical theme by a composer (one finds a good

example of this type of research in Beethoven’s sketchbooks), the basic

research on a phrase by a performer (think of the instrumental exploration of

Glenn Gould or of Harnoncourt), or even the research

for a libretto likely to carry an opera (think of Wagner or Schoenberg). In

short, it is not this type of musical research that limits itself to a given

work.

I would like to speak to you about a

more global research, which is likely to embrace multiple musical works, a

research configuring a compositional project of vast dimensions, a research

necessitating an interlacing between compositional practice and what I call musical intellectuality (that is to say

a formulation, in ordinary language - the same one in which I speak to you - of

musical issues). Or, to put it simply: a research that articulates musical practice

and theory on a grand scale.

The

difference, in music, between narrow research (on a theme, a phrase or a

libretto) and global research on a new compositional orientation can be

compared to the difference, in mathematics, between narrow research into a particular

demonstrative sequence and global research into a new theory - I will return to

this.

Certainly,

you know better than I that these two dimensions of mathematical research are

not without connections (demonstrating a given sequence can require a new

theory, and no new global theory is without its local demonstrative

inventions), but they set the two poles between which each real research must

learn to circulate.

In this way, in music as in

mathematics, a global research

associates theories and models, hypotheses and experiments, intuitions and

verifications. More specifically, as I have indicated, a significant musical

research associates composition and intellectuality, works and texts, writing

and listening.

I am

talking about compositional research

and I therefore exclude here musicological

research as well as technological research

(such as, while very interesting, is led at Ircam in

Paris, as in other equivalent centres of research around the world).

After this little comparison between

musical and mathematical research, a short note on their differences.

As you might expect, the opposition

between compositional and mathematical research rests on the criteria of validation

for the results of the research in question: music does not dispose of an

equivalent of mathematical demonstration, music does not produce its own

theorems, and one could also not say that it produces its own conjectures (if

it is true that in mathematics statements of conjectures and of theorems are

always equivalent [3], the

first being distinguished from the second only by the fact that they are awaiting

demonstration or refutation). In truth, music [4] knows

nothing of these demonstrations.

The criteria of validation of musical

research are thus rather to search elsewhere:

- On

the one hand, on the side of a certain practical success: do the works produced “work” musically? But what does it mean exactly to

“work”? Musicians do not agree on this term (like mathematicians can agree on

the term “to demonstrate”).

- On

the other hand, on the side of a certain productivity:

are the ideas implemented musically stimulating? But, even there, the

stimulation will not be the same for all composers and the productivity criteria

will then no be massively shared by the musicians.

In truth, behind this question of

properly musical criteria runs the great question of beauty: does musical beauty always constitute a criterion of

validation of a compositional experiment, leaving it to share what musical beauty really means?

Now the point today is that there is no

more agreement between musicians on the notion of beauty as a criterion of

compositional success. One can even uphold that the contemporary is detached

from the modern around this precise point: where the modern (we would say, in

music, starting with Schoenberg) aims to recapture from classicism the flame of

beauty to found a specifically modern beauty, the contemporary (we would say,

in music, starting from 1968) disqualifies the opposition between the beautiful

and the ugly to promote the notions of innovation

and of creativity: a musical

experience will then be judged as novel and thus interesting, or as academic

and thus uninteresting, but the criterion of beauty will no longer be

considered pertinent.

One

can however claim that beauty constitutes the properly artistic form of truth:

so in art, the name of truth is beauty.

To recuse the criterion of beauty from the contemporary musical experience

would be equivalent to recusing the criterion of truth from the scientific

experience - you have a sense that the degree of ideological upheaval in this

way operates from the modern towards the contemporary…

This ideological upheaval has the consequence

that all compositional research becomes today ipso facto a research on the very criteria of what musical composition still means (the

ideology of the contemporary, here, promises - contrary to the modern - performance

against interpretation, the openness of new inscriptions against the closedness of ancient scores, mobility between artistic

practices against the fixity of delimitations between different artistic

worlds…).

My own research on the notion of

heterophony is part of such an ideological context: it is an attempt to revive

musical modernity, to take up the compositional questions left fallow at the

end of serialism (roughly from the turn of the 60s) against a nihilistic figure

of the contemporary that would like to impose itself as the only inventive

current.

Let us now turn to the more concrete

figure of this compositional research which has been

mine for some years.

A compositional research

Let us start with a quotation from

Pierre Boulez, taken from the last pages (written in 1960) of Penser la musique aujourd’hui:

In my opinion, a certain lack of homogeneity of voices has

been confused with the abandonment of one of the richest principles of Western

music: two or more "phenomena" evolving independently of one another,

without ceasing to observe between them a responsibility of each instant. It is

thus necessary to conceive of the transformation of the notion of voice, not to

envisage its abolition, which annihilates one of the most important domains of

the dialectic of composition.

Boulez,

in saying this, orients musical composition according to three propositions:

1. Composition

must continue (rather than abolish) the ancestral principal of musical responsibility between independent

evolutions.

2. To

do this, composition must extend this principle of responsibility to non-homogeneous evolutions.

3. This

extension passes through a transformation (rather than an abolition) of the old

notion of voice.

Let us

summarize this in the following program: the dialectic of composition must take

up the old musical responsibility between independent voices and extend it to

heterogeneous voices, which then passes through a transformation of the ancient

notion of voice.

This

program is then explicitly opposed to a “contemporary” program that prefers to purely

and simply abandon the notion of co-responsibility and to abolish the notion of

the musical voice.

Incidentally

- we can distinguish three ways of revolutionizing a given domain:

1. A

revolution by destruction then reconstruction - this is, in politics, the paradigm

of insurrectional revolutions (from the French Revolution to the Russian

Revolution of 1917), destroying a given State to reconstruct in its place a new

type of State.

2. A

revolution by abandonment and then displacement - this is, in politics, the paradigm

of "liberated zones" (from anti-slavery uprisings to a long sequence

of the Chinese Revolution).

3. A

revolution by extension-adjunction - this paradigm is found this time in

mathematics (see for example the extension of the rational numbers to the real

numbers by adjunction of Dedekind cuts).

It can

be said that musical modernity separately experimented with these three types

of revolution: respectively with Boulez, Pierre Schaeffer and Schoenberg.

It can

also be argued that a new type of revolution should aim at combining these

three types rather than holding them incompatible or practicing them

separately.

Let us then reformulate the orientation

suggested by Boulez in order to better sketch out our research program: it is a

matter of extending polyphony (which practices collective responsibility

collectively) by adjoining new types of vocal configurations.

Just

another note: the musical “voice” is here a discursive notion and not at all

physiological.

Vocal configurations

What kinds of vocal configurations do

we have in music? Essentially five.

1. There

is monophony, or a configuration of

one voice - that's our singleton.

2. There

is then homophony, or a configuration

of several identical voices, that is to say, all playing the same thing - exemplarily

the two crucial moments in Wozzeck where the whole orchestra converges on the same B - that

is our One.

Two

examples of homophony

Verdi : Nabucco (Chorus of Slaves) [5]

Berg : Wozzeck (unison on a B) [6]

3. There

is then antiphony or the configuration

opposing two voices to one another, either simultaneously or alternating - see

the old Responses, the contrast refrain/couplets, etc. - this is our 1 + 1 = 2

4. There

is also polyphony or the

configuration made of multiple different voices (they don’t play the same

thing) but cooperating in the same global realisation - this is exemplarily the

case of the different voices of a choral or of a fugue - this is our plural.

5. Finally,

there is cacophony, or the configuration of voices anarchically piled up and

rivalling each other - for example, the Épode of Chronochromie (Messiaen) - this is

our pure multiple.

Example

of cacophony

Épode

of Chronochromie

(Messiaen, 1959–60) [7]

In

this way we distinguish the plural - the

repetition of the same type of term (1 + 1 + 1 + 1 ...)

- and the multiple - the simple

overlapping of terms of disparate types. Thus, the plural mobilizes the similar

and the multiple the heterogeneous - for example, two tonal voices will be dissimilar if they do not share the same

tonality and two voices will be heterogeneous

if for example one is tonal and the other dodecaphonic.

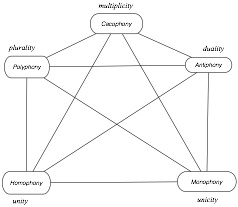

Let us summarize: Music knows the

unicity of monophony, the unity of homophony, the duality of antiphony, the plurality of polyphony and the multiplicity of cacophony.

We can

summarize these five vocal configurations as follows:

In so doing, we formalize oppositions

and connections that structure our five vocal configurations, but in reality

this draws a well-known figure from logic: that of a hexagon of oppositions,

which indicates to us the existence (at the bottom) of an absent vertex making

a strong opposition with cacophony.

It is this vertex that we are going to

add to our plan: let us call it (by a neologism) juxtaphonie - which suggests a notion of collage in this type of vocal collective (see for example Charles

Ives or Bernd Alois Zimmermann).

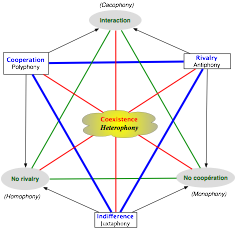

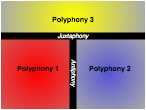

We can thus schematise the following

hexagon (which will this time formalize different types of qualitative relationships

between voices rather than different quantities of voices):

It is the very game of this hexagon in its entirety that we now propose to

call heterophony.

Before justifying the name heterophony globally given to this

hexagon, let us examine the logical properties of this hexagon of oppositions.

- The

hexagon rests on three vertices formalizing three collective logics

incompatible two by two: polyphony carries

cooperation (between the different voices), antiphony

carries rivalry between them and juxtaphony

carries indifference.

- Each

pair from these three vertices configures a vertex of another type which formalizes the interaction between different voices (common interaction in

polyphonic cooperation and antiphonic rivalry), the non-cooperation (common to antiphonic rivalry and to juxtaphonic

indifference) and the non-rivalry

(common to juxtaphonic indifference and polyphonic cooperation).

- These

three new vertices are in a logical relation of subcontrariety

(globally incompatible, they remain compatible two by two). They include our

three remaining vocal configurations: cacophony

taken as an emblem of the interaction between different voices, homophony as the emblem of non-rivalry

and monophony as the emblem of non-cooperation.

- Each

of the six vertices is in strong contradiction with its symmetrical opposite:

one must choose between polyphonic cooperation or non-cooperation of

monophonies, between antiphonic rivalry and homophonic non-rivalry, between

juxtaphonic indifference and cacophonic interaction.

In total, our formalization classically

distinguishes:

- two types of vertices: the

"products" inscribed in blue in a white rectangle and the

"vertices" inscribed in green in a gray

oval;

- three types of opposition between

vertices: the contradictions (in red) between a "product" and a

"sum", the contraries (in blue) between the "products", and

subcontraries (in green) between the "sums";

- a type of implication between

vertices (arrows in black from a "product" to a "sum") - for

example: "if cooperation, then interaction and/or coexistence" ...

Heterophony

What then does “heterophony” name?

Heterophony

here names a remarkable property of this logical hexagon of oppositions: its Borromean knot structure - it is the mathematician René Guitart who untied it [8].

This means that cooperation, rivalry and indifference (or polyphony, antiphony

and juxtaphony) can be tied in pairs by the play of the third.

It is precisely this global property of

Borromean interlacing that I propose to call heterophony.

Heterophony

will therefore be defined here as this new global type of vocal

collectivization which braids (Borromeanly)

polyphonic cooperation, antiphonic rivalry and indifferent juxtaposition

between voices of all types.

Thus heterophony is the interlacing of

collectives of different types. It designates a global Collective made of

sub-collectives - hence its reasonance with

the political idea of people

...

An

interesting and unexpected musical example of such heterophony can be found in

the discourse of the burning Bush intervening at the very beginning of Moses und Aaron.

Three

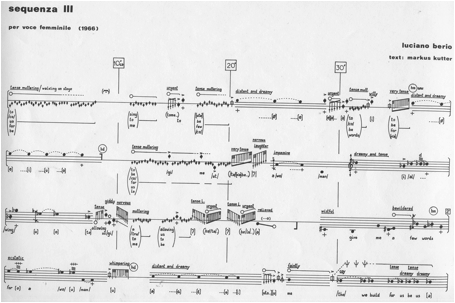

examples of heterophony

Spoken/sung

heterophony: the burning Bush in Moses

und Aaron (Schoenberg) [9]

Heterophonic voice: Sequenza III (Berio) [10]

Heterophony in improvisation (jazz): Art Ensemble of Chicago [11]

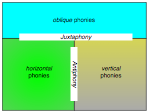

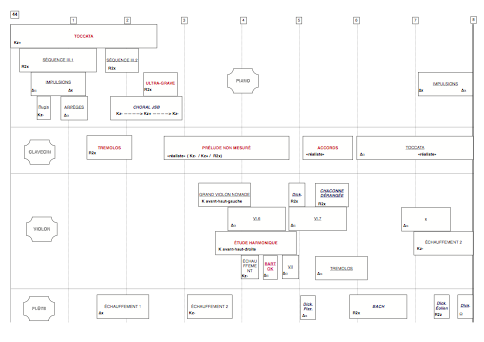

To fix these ideas pedagogically, let

us advance these two minimal matrices of heterophony, which assemble in

different ways (simultaneously and successively) different types of vocal

collectives (or phonies):

Here is an example of such a

heterophony, extracted from my Ricercare

hétérophonique:

(juxtaphony between strings & antiphony with the piano)

In doing so, I propose to hear heterophony in the strong sense of a new

type of musical discourse.

The issue of heterophony, as we have

seen, is to tie or intertwine different heterogeneous vocal configurations - one

could say: different heteronomous musical discursivities.

But in doing so, it is a question of producing a vocal ensemble

which affirms a new type of global unity between its different vocal

configurations and not one that is content with a juxtaphony or a cacophony of

different polyphonies. The formal

name of this new heterophonic type of unity is knot; its musical name is discourse.

It will therefore be said that the stake of this tying will lie in its capacity

to compose a new type of discourse: a heterophonic

discourse, which cannot be limited to a heterophony of different discourses.

In the

example given above, it is therefore necessary that the ensemble composed of

the two successive interventions of the strings and the simultaneous

intervention of the piano make, all together, “one” musical discourse (in a

new, enlarged sense of the word discourse) and this, beyond the

disparity of the three remarks thus reported.

To

give two political equivalents of this question:

o Is

it legitimate to continue to speak of the "Chinese revolution"

(1927-1949) once the three types of revolution which are combined in it

(successively or by partial superposition) have been identified?: one of abandonment-displacement, the other of

destruction-reconstruction, the third of adjunction-extension;

o It

is also a question of being able to think of the collective existence of a

people not as a collective of individuals (the serialized mass of Sartre in the

Critique of dialectical reason) but

as a political unit of a new type between different mass collectives (workers,

peasants, women, young people...).

This is the formal challenge of the

compositional research in question.

The formalization of research, the

creation of compositional "models" for this formal theory of heterophony,

is at stake in musical compositions that concretely support this research.

Before returning to it, a few words about other uses of the term heterophony in the musical field.

The meaning I give to heterophony differs considerably from

the traditional musical use of this term. The term comes from ethnomusicology,

naming a sort of approximate homophony - when large groups of musicians play

vaguely in unison. Here, the hetero-

prefix no longer names alterity in so far as it

opposes the same homo- of

homogeneity, but denotes an alterity in a homogeneity, a localized alteration

of a global homogeneity. The two meanings of heterophony - the ethnomusicological

sense and the compositional meaning that I give it - are therefore radically

heterogeneous.

Two

examples of heterophony in the musicological sense

J.-S. Bach - Cantata BWV 80 "Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott", Aria for soprano with oboe obligato

Mozart - Piano Concerto in C minor, K491, first movement, bars 211-214

I have

presented my musical research to you by privileging its formalized approach, in

particular by privileging a deductive form of mobilized formalization. But this

is of course a rhetorical presentation of the first results, in no way a

chronological account of the research in question.

In

fact, the idea of heterophony, as

clarified by the formalization here outlined, proves to have always been at

work in my compositions, such that the research in question here is a

revelation of intuitively pre-existing hypotheses.

In my

early compositions, the latent interest in this heterophony, which I was not

able to name until recently, was already there: for example, in Deutschland (a work from thirty years

ago). And I can now retrace a great part of my work as a composer by following

the red thread of this idea.

I will

not do it here, but ultimately this late formulation of an intuition that is

always-already at work would validate the well-known hypothesis that we would

have only one idea in all our life!

Three

examples of heterophony in my precedent works

Cadence of Duelle (2001) [12]

Ten voices in four configurations : two heterophonic (4 pianos | 4 violins) and two monophonic-polyphonic-antiphonic (harpsichord | flute)

Instress (2007) [13]

Heterophony of three configurations: polyphonic (three voices: string trio), monophonic (flute) and variable (piano)

Hétérophonie presto (2016) [14]

Heterophony by collage of five

configurations:

–

heterophonic (chorus of six

languages)

–

antiphonic (counterpoint of two

monophonic songs)

–

polyphonic (Magnificat - Bach)

–

antiphonic (two musical voices

coming from jazz)

–

homophonic and/or polyphonic (Presto, for percussions).

Reasonances

To

emphasize this point, I will even tell you that I have recently realized that

my whole personal and individual life has been guided by this principle of heterophony if it is true that for

decades now I have led a life interweaving six simultaneous voices, sometimes

polyphonically unified, sometimes cacophonically

divergent, sometimes indifferently juxtaposed, a life that can be called

"heterophonic" since it intertwines daily survival (waged work and daily

tasks), a life as a parent (to numerous offspring), a life as a lover, a life

as an activist, a life as a musician and a life as an intellectual (who is

interested in mathematics, for example).

I have

already suggested the reasonances

of this notion of heterophony in political matters.

I

would like to point out that I am organizing a fifty-year anniversary week of

the fifty years since May ’68 which will be called Hétérophonies/68: its title highlights the reasonances of the notion of

heterophony with the exuberance of the collective thought freed during this

historical uprising.

But I

would like to conclude by saying how this same notion of heterophony could also

concern certain aspects of mathematical research.

For

this purpose, I would like to examine the heterophonic dimension of two

mathematical theories: in analysis, the theory of integration and in

arithmetic, the theory of extensions of numbers.

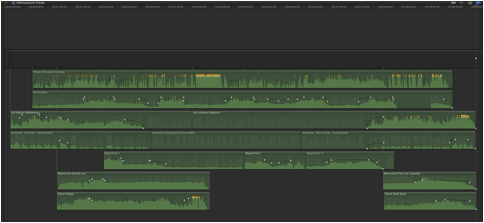

Theory of Integration

We can

classically distinguish three times in the theory of integration, three times

which have deposited three different conceptions of integration indexed by

three proper names: Riemann, Lebesgue and Kurzweil-Henstock.

As we

know, these three theories of integration are partly compatible, even

complementary (Kurzweil-Henstock in a sense "completes" Riemann by

the introduction of a gauge on the abcissa’s axis),

as rival parties (Riemann and Lebesgue "rival"

with respect to the privileged axis of integration: abcissa

or ordinate?). Could one not then consider the interweaving of these three

mathematical "voices" as configuring, in total, a heterophonic

conception of integration?

This

could then be drawn as follows:

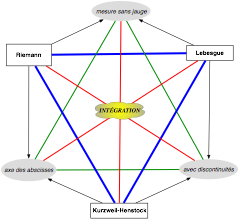

Theory of numbers

Let us

now take the arithmetical theory of numbers which

proceeds by successive extensions from whole numbers - let us say ℕ,

ℤ,

ℚ,

ℝ,

ℂ.

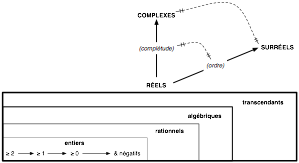

We can

diagrammatise this in a little more detail:

Do we

not see here, too, the way in which a vast theory is developed heterophonically by playing simultaneously with different

numerical configurations which maintain different

relations between them?

- relations of polyphonic cooperation (to

pass, for example, from rationals to the reals by

Dedekind cuts),

- relations of antiphonic rivalry or juxtaphonic

coexistence (depending on whether one extends ℝ

to the body of the complexes - losing then the relation of order - or to the

body of the surreals - losing algebraic completeness

this time).

So it

seems - and I will conclude on this - that compositional research aimed at

taking up the old notion of musical discourse and extending it into a

heterophonic discourse, intertwining polyphony, antiphony and juxtaphony, can -

beyond its own musical productivity (which is, of course, its main, immanent

criterion of success) - resonate with similar concerns in widely differing

areas of thought.

At

this point, the risk would of course be to constitute the musician - in this

case the composer - as a prophet of humanity (it is known that Jean-Philippe

Rameau began to drift in this direction from 1749, d’Alembert

rightly immediately set himself against these new claims of musical

intellectuality to try to set the course of the sciences of the time).

Let

us suggest that the risk nowadays would be all the greater for musical intellectuality that musicians could be

tempted to substitute themselves for the contemporary poets deploring melancholically

the end of the "age of the poets".

The

musician must therefore drastically self-limit this musical research on the

notion of heterophony. But this does not prevent him from addressing to the

mathematicians some friendly gesture of the hand to signify to them that they

are not alone in trying to invent a new modernity of thought.

Thank

you.

***