Is Schoenberg Wagner’s future ?

(composer, professor at l’École

normale supérieure de Paris)

What do they have in common?

Analogies

Continuation

The interval

of time that separates them

Three steps

The twilight-Wagner

What is

twilight?

Resistance,

perfecting and prophecy in Wagner

Dawn-Schoenberg

What is it

[than] a dawn?

Second string

quartet as dawn

Musical dawn

The between Wagner-Schoenberg

The wagnerian

references in Schoenberg

In the second

string quartet

Distance

References

Before 1908,

during “the night”…

Transfigured

night?

The plot

Two nights

Romantic

night

Transfigured

night

The music

Small analysis

Parsifal

transfigured by Schoenberg?

What transfiguration?

Music doesn’t

think alone

Wagner and

the drama

Schoenberg

and the diagonal

french

institute alliance française

Wagner, our contemporary

IV - Wagner: Visionary or Gravedigger?

Monday,

May 1 at 8pm | Florence Gould Hall | In German

Enjoy a program of groundbreaking music; then decide for yourself about

Wagner’s position in the subversion of tonality at the turn of the 20th

century. The evening’s program includes Liszt’s Bagatelle Without Tonality and Wagner’s Dedication

for Piano.

LISZT – La lugubre

gondole & Romance sans paroles, for cello and piano

LISZT – Am Grabe

Richard Wagners, for string quartet and harp

WAGNER – Dedication, for piano (Bunte Blatter)

SCHOENBERG – Verklärte

Nacht, for string sextet

SCHOENBERG – Quartet No.

2, for soprano and string quartet

PRE-CONCERT LECTURE Is

Schoenberg Wagner’s Future?

François Nicolas, composer and professor at l’École normale supérieure de Paris

Monday, May 1, 6pm | Florence Gould Hall | In English

Beyond some shared personality traits, Wagner’s and Schoenberg’s compositions

are clearly dissimilar, as are their roles in the history of music. Indeed, Debussy

saw “dusk” in Wagner and Berg presented Schoenberg as “dawn.”

What is there to expect of the relationship between a crepuscular-Wagner and an aurora-Schoenberg? And how to imagine the “musical night”

that have separated them?

Is

Schoenberg Wagner’s future ?

What has happened between Wagner and Schoenberg ? What

kind of continuation, what breach

between the two

of them ?

“Between Wagner and Schoenberg”? This “between” should be taken in two ways:

·

as

what they could have in common,

·

as an

interval of time that separates them.

Therefore two questions:

- what is it that Schoenberg and

Wagner have in common?

- how does Schoenberg relate to the musical

problematic unfolded by Wagner?

What do they have in common?

Let’s do a list of common traits between the two men and their two Works.

Analogies

· They have both written the libretto

for their operas (see Moses and Aaron for Schoenberg).

· They both combined composition with

a theoretical activity.

· They both made a great effort to

surpass the works of their youth (see the rupture for Wagner around 1849 and

for Schoenberg around 1923).

· They both knew exile, being chased

out of their countries (as a banned revolutionary in the case of Wagner, as a

Jew in the case of Schoenberg).

· They both showed a close interest in

politics for some time and then stayed away from it (from 1849 to 1851 for

Wagner, from 1933 to 1938 for Schoenberg).

· They both were passionate about

love, the differences between sexes and largely composed on this theme (for example

Transfigured Night,

which we will listen to this evening).

· Neither of them showed any interest

in the science of their time.

· They were both emancipators of

dissonance and chromatism.

· They both bet on a renewed thematism

to emancipate themselves from other musical dimensions.

· They both set themselves up to

compose “music of the future”.

· They both have created their own musical

institutions: Bayreuth for Wagner, The society for private musical performances for Schoenberg.

· They both bet on the ratio of the

music to the distinctiveness of the prose and the voice to encourage music to

emancipate itself (characteristically for Schoenberg the second string quartet

that we will listen to this evening).

Continuation

Schoenberg is conscious of its closeness with

Wagner. He declares himself as following the footsteps of Wagner:

“From Wagner [I have learned]:

1. The way to make possible treating the

themes to obtain the maximum expression; the art to write to this effect.

2. The relationship between notes and

chords.

3. The possibility to treat themes and

motives […] in a way that would let us to superimpose them on a harmony without

worrying about the dissonances that would result.”

More specifically, Schoenberg is often regarded

as having constantly oscillated between Wagner and Brahms, between these two

great figures in the music of the second half of nineteenth century.

For example, according to Boulez:

“For Schoenberg the umbilical cord with

Wagner-Brahms will never be totally cut. A slow oscillation between the first

and the second of these predecessors will remain the most characteristic in his

long career.”

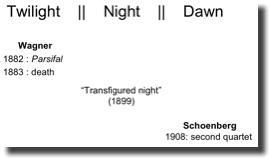

The interval of time that separates them

Let us look quickly at what covers the time

that separates them.

Let us recall certain dates:

· Parsifal is written in 1882 and Wagner dies

one year later, in 1883.

· The first significant work of

Schoenberg – the Transfigured Night – dates from 1899 (this is his opus 4,

preceded with three opuses consecrated to the lieder).

So, almost twenty years separates the end of

the work of Wagner and the beginning of that of Schoenberg, and I suggest that

you regard this as a kind of a night separating the twilight-Wagner and the dawn-Schoenberg.

In fact it was Debussy who started the idea of

Wagner as a twilight, and Zemlinski (and later Berg) the idea of Schoenberg as

a dawn.

There would be then between Wagner and

Schoenberg a night of almost a quarter of century if one considers that dawn-Schoenberg starts with his second string

quartet (1908) which we will hear this evening.

This is a

hypothesis that I suggest we examine: the connection of twilight-Wagner and dawn-Schoenberg, through a night which proves

itself transfigured.

Three steps

I will proceed in three steps, asking myself

successively:

1.

In

what way was Wagner a twilight?

2.

In

what way was Schoenberg a dawn?

3.

What

kind of juncture there is between such twilight and such dawn? In what way the oncoming

day Schoenberg

should be associated with the ending day Wagner via that night that should have been a pivot

between nineteenth and twentieth centuries?

The twilight-Wagner

For Debussy, associating the image of a

twilight with the Work of Wagner was a way of depreciating. For him, it was a

way to suggest that the music of Wagner was without future and its destiny

closed.

But in fact Debussy didn’t believe in this

diagnosis: to realize that, it suffices to discover how much his music is intimately

inspired by Tristan and Parsifal, especially in his masterpieces which are Pelleas and Jeux – in this respect, the book of

Robin Holloway (Debussy and Wagner) explains in detail how much the writing of

Debussy is closely inspired by Wagner’s.

If it’s true that Wagner was a twilight, I

would like here to raise the notion of twilight, demonstrating that a twilight is not

necessarily what Debussy suggests.

What

is twilight?

Twilight, in fact, is not always a moment of

renouncement; it’s not necessarily an instant of “no future”. On the contrary, a twilight could

be regarded - should be regarded – as a moment coupled intimately with resistance,

perfecting and prophecy.

· The twilight actually is resisting

the oncoming night rather than surrendering to it. According to René Char, “for

a dawn, it is the oncoming day that is a disgrace; for the twilight it is the

night that gobbles it up”. The twilight resists the menacing night; the twilight protects still

for some moments the day that is threatened. So, the twilight is not longing

for the night, because, as René Char writes, for the twilight the night is a

disgrace rather than an apotheosis or an opportunity.

· So, the twilight resists the

oncoming night while protecting the ending day till the last moment. How does

it protect it? By perfecting and putting the finishing touches to the day, by

carrying out the given tasks to its final conclusion, so that they will not

stay unfinished.

· Finally, the twilight forecasts, not

what there will be tomorrow, later – the twilight doesn’t know what will come

after the new and distant dawn – but what will remain of the day that the

twilight perfects; the twilight is a prophecy, not in the future tense but in

the future perfect: “that day would have been worthy of posterity, as this and

that would have been what this day hands down to posterity”.

Resistance,

perfecting and prophecy in Wagner

Wagner is a good example of twilight because

the Oeuvre-Wagner - particularly his last opus (Parsifal) - interlaces a resistance, a

perfecting and a prophecy.

· Firstly the work of Wagner resists

the superficial and frivolous concept of the music of his time, be it a simple

amusement or an academism that introspects on itself.

· Secondly the work of Wagner

perfects: it achieves what Wagner called “opera as a drama”, that means an affirmation that

the music can talk to the world and with the world, that it can be autonomic

without being autarchic.

· Finally the work of Wagner

forecasts: it foretells not the coming of chromatism (therefore Schoenberg) but

it foretells that what counts in his work will remain and stay able to question

the composers and creative artists of the next century (which means the twentieth

century). On this idea I have given a course of lectures (in École Normale

Supérieure on Ulm

street in Paris) which explains in what way Parsifal is a work of music for today and

not for the museums.

To see in twilight-Wagner not a museum piece but a musical

chance to hope, is, in a nutshell, what Charlie Chaplin tells us in his film The

great dictator: he

indicates that one should tear Wagner away from the hands of Hitler, and that

there is hope for a free future if following the directive “Listen to

Wagner!” (in this

instant: “Listen to the prelude of Lohengrin and what comes after!”)

It’s important to remark that this prelude from

Lohengrin that

concludes the film in a tonality of hope has previously accompanied the famous

dance of the dictator, playing with the balloon-globe, what underlines that

Charlie Chaplin wanted to take over the music of Wagner that Hitler wanted to

monopolize.

Dawn-Schoenberg

In what way, now, was Schoenberg a dawn?

What

is it [than] a dawn?

A dawn – what is it exactly?

This is what the french theatre tells us:

[The woman Narsès:] “What is it called, when a

day gets up, like today, when everything is a mess, everything is confused, but

one still breathes the air, when everything is lost, when the city burns, when

the innocents kill each other, but when the guilty agonize, in a corner of a

day that gets up?”

[Electra:] “Ask the beggar, he knows”.

[The beggar:] “It has a very beautiful name,

woman Narsès. It is called the dawn.”

Giraudoux (Electra, II.10)

The dawn, it’s an announcement that something

is coming after the dark, deaf and brutal night.

And a dawn, subjectively, is this:

“Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open

road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I

choose.”

Walt Whitman (Song of the Open Road; 1856 - Leaves of grass)

A dawn, it’s an enthusiasm of a new jump, it’s

an exaltation of appropriating a new territory in big stride.

Second

string quartet as dawn

The second string quartet, that you are going

to hear this evening, is clearly a such dawn, and more precisely, this type of

dawn that reveals itself since the fourth movement – Transport [Entrückung]

- from what

constitutes at the beginning a classical string quartet, witnesses a soaring

soprano that sings the following words:

“I

feel the air of another planet.

[…]

I see the hazy vapors lifting

Above a sunlit, vast and clear expanse

That stretches far below the mountain crags.”

Moreover, this dawn that declares the fourth

movement follows a third movement that is put clearly, by the poem Litany, under the sign of a desolate

night:

“Deep is the sadness that overclouds me.

[…]

Long was the journey, weak is my body,

[….]

Empty my hands, and feverish my mouth.

[…]

Lend me thy coolness […] send forth the light!”

Musical dawn

How does the fourth movement carry out

musically the dawn that the poem declares?

· First of all, by unexpected

irruption of a soprano in a string quartet that in itself suffices to “illuminate”

the whole work.

· Than, by atonality: this is the

first piece of music - first important piece because the ‘Bagatelle without

tonality’ of Liszt that we will hear this evening is a little one, without true

ambition, a curiosity, not a masterpiece, as the second quartet of Schoenberg -

to be without signature, that

means without sharps and flats at the clef, in other words without a defined

tonality. So, dawn takes here a form of a leave given to tonality.

*

What does or doesn’t this dawn owe to Wagner?

Would it be, like the dawn that was equally declared to be Debussy, a dawn

separated from the former twilight-Wagner, a new youth of the day oblivious of the

former day that is already definitely buried?

Shortly, between twilight-Wagner and dawn-Schoenberg, is there a bridge lanced over the

night that is separating them?

The between Wagner-Schoenberg

This opens two questions:

· Are the musical resources that

Wagner has enclosed in Parsifal in a certain way reactivated by Schoenberg?

· And in return, are the resources

mobilized by Schoenberg for his new day related to those that Wagner has mobilized

in his Work?

Let us begin by the second one.

The

wagnerian references in Schoenberg

In the second string quartet

We begin by examining the references to Wagner

in the second string quartet of Schoenberg.

Distance

It’s true that in this quartet there is a whole

part of dawn-Schoenberg that doesn’t owe anything to twilight-Wagner.

· So, the way Schoenberg progressively

refines his material – it’s enough to compare the means gigantic (precisely

wagnerian) of Gurrelieder with those of the string quartet – doesn’t derive at all from a

wagnerian gesture: Schoenberg needs this kind of economy of means to press hard

the new type of musical discourse that he will invent, keeping distance from

the security that until than was offered by tonality.

· The desire itself for atonality, for

music free, liberated from the tonal stress, doesn’t come from Wagner, always

solidly camped on the tonal architecture..

References

However this quartet stays pregnant with a

wagnerian harmonic perfume. Let me give two examples.

· One can notice that the quartet

starts under the sign of sequential work that Wagner has carried on a large scale:

thus all the first measures of the quartet repeat the same phrase, first in F

sharp minor, then in A major via a unison on C natural (to exploit the minor

thirds stacked up); in short, Wagner has never done differently at the

beginning of Tristan (A minor, then C minor…)

Examples

Schoenberg : beginning of the second

quartet

Wagner : beginning of Tristan

· Later, in the quartet, Schoenberg

puts his themes under a treatment that one could call leitmotivic since not only the first theme of

the first movement is taken again, varied like theme of the third movement –

cyclical logic - but it reappears superposed on its second part – logic equally

wagnerian, this time of weaving a polyphony from a thematic network.

Example (2° quartet)

the beginning of the third movement is build by

counterpoint of precedents themes :

So it’s true that the shadow of Wagner

continues to hang over the gesture of dawn.

But what had been of Wagner’s influence on

Schoenberg before his second string quartet? What had there been during the

“night” separating the twilight 1882 and dawn 1908?

Before 1908, during “the night”…

It’s striking that one more time Schoenberg

responds to it very explicitly since he composes a work that reveals itself

being a transfigured night!

So the program of today’s evening is

intelligently conceived since it will allow us to hear two works of Schoenberg

that not only illuminate musically the connection of Schonberg to Wagner but,

more so, they tell exactly what they do – two works that we could call “performative”:

telling what they do and doing what they tell – since one (the opus 4 of 1899)

declares to transfigure the night (meaning, as we will see, to liberate from

the post-romantic obscurity) and the other (the opus 10 of 1908) declares

passing from a night, hollow and weary (Litany), to a new day, open for the new horizons (Transport).

Transfigured night?

For Schoenberg, what is it than a transfigured night, what is

it his Transfigured Night [Verklärte Nacht] ?

The plot

Let us start off with the plot of this work,

however with no words to be sung, nevertheless very much referred to a poem by

Richard Dehmel.

This poem speaks of the night encounter of two

lovers. The heartbroken woman tells the man that she bears a child that is not

his. The man declares that his love will make this child of a stranger his own.

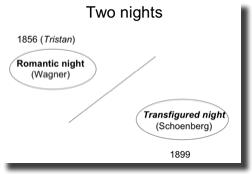

Two nights

Romantic

night

One can see how this condensed little drama

escapes the logic of a romantic night (of which Tristan sets an eternal model) where two

lovers unite under the horizon of professed death: the romantic night was in an

exemplary fashion without dawn.

Transfigured

night

The transfigured night surmounts this romantic

night since love is precisely not what unites a pair of lovers but what makes

true of its disjunction at the mercy of a child that circulates from one to the

other.

So the transfigured night is at the same time

an emancipation of love from its romantic fusing figure and an emancipation

from a romantic vision of the night like alpha and omega of the day that

precedes it. It’s the transfigured night that carries the child conceived by

the passed day towards the light of a new day that announces itself.

Why not to regard all of this as a transparent

allegory, especially as for Wagner the music was precisely a woman, a woman

impregnable by the poet? Why not regard the child born by a woman and adopted

by the lover as a work handed down by romantism – wagnerian work, to be precise

– that the music transmits into the new century?

The music

In what way the musical piece named Transfigured

night accomplishes

this program? What is it that it’s transfiguring, particularly of Wagner’s

music? In what way does it enter the retroactive composition with the second

string quartet and singularly with the dawn that constitutes the fourth

movement?

Small

analysis

Schoenberg himself guides us on this path when

he writes:

“My Transfigured night brings forward Wagner in its

thematic treatment of a cell developed on a changing harmony”.

This harmony was so new that the piece was

refused to be presented because of a chord not classified, a dissonance “not

cataloged”!:

Thus in 1898 Schoenberg strayed away quite a

bit from the paths guided by tonality. But, as indicated, it’s in 1908 when he

crosses over the Rubicon.

It’s easy to see that Schoenberg in fact has

just extended what Wagner has largely deployed in Tristan and equally in his Parsifal (what is less noticed), for example

in the second scene of the transformation, in the middle of the third act,

where the chromatism gets wild.

The musical transfiguration of Transfigured

night is associated

with the clearing brought by D major in the fourth part of the piece, in the

moment when the poem underlying the piece puts these words in the mouth of the

man:

“The child that you conceived,

let it be no burden to your soul;

oh, look, how clear the universe glitters!

There is a radiance about everything;

[…]

a special warmth glimmers from you

[…]

It will transfigure the strange child.

[…]

you have brought the radiance into me.”

In a certain way, one should recognize that

this piece announces rather a transfiguration than executes it musically: a

modulation from minor to major is in fact too conventional to be able to

constitute by itself a transfiguration, that means an appearance by

transparence of a new musical figure. This kind of modulation declares a

transfiguration without realizing musically what it’s talking about.

So one needs to wait for the second string

quartet of Schoenberg to succeed to transfigure Wagner.

Parsifal transfigured by Schoenberg?

In a way, one could in fact hear the last

movement of the second string quartet - the one where the soprano soars emerging

from the bosom of quartet for strings - as a transfiguration of Parsifal.

In fact, the absolute contrast of the forces

between the big wagnerian orchestra and a diagram of a string quartet constitutes

a frame adjusted to the principle of a reappearing idea under the new day, the

musical idea transfigured by its trimming to a new body.

What transfiguration?

What idea, inherited from Parsifal, is transfigured by the quartet of

Schoenberg?

What is this musical idea accomplished to

perfection by twilight-Wagner and now spurts up transfigured by dawn-Schoenberg?

Music doesn’t think alone

It seems to me that music doesn’t think alone;

music wouldn’t know to think lastingly all by itself. Music thinks with the

others thoughts, singularly with the poetic thought, especially when it comes

for the music to cross over to a new stage of its unfolding.

For the music, the way of thinking with the

poem happens through the voice.

In fact a force of the synthesis of which the

music disposes happens through the voice, because in the music it’s the same

voice which sings and which talks simultaneously.

So, the specific point that binds Schoenberg to

Wagner has to do here with using the voice and the text that it sings when it

comes for the music to reach the new laws.

When it comes to make a step to cross over the

void, either to take up a new world (what did J.-S. Bach with his Well tempered

keyboard) or to

open a door towards what will become a new world, when it comes to move the

musical frontier, to win for the music new sound territories – like an american

image of a “new frontier” that moves incorporating new land -, there the

musical treatment of a voice supported by the text can become a crucial agent.

Wagner and the drama

Wagner made the voice his principal agent of

the synthesis, particularly his dramatic agent since the word “drama” for

Wagner describes a synthesis of music, poem and theatre. To make this synthesis

work by the voice and around the voice, Wagner had broken down the old logic of

the aria and of the pretty melody and has invented “the unending melody”. Parsifal achieves this new musical logic to

perfection.

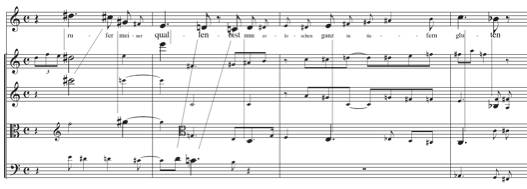

Schoenberg and the diagonal

In Transport Schoenberg transfigures this idea of the voice

as an agent of the new synthesis. He realizes this idea, and I would like to

conclude on this remark not under the form of an unending melody but under the

one that I suggest to call diagonal since the soprano voice traverses inside the

quartet, its harmony, its motives and its rhythm.

Thus Schoenberg creates a new agent of

synthesis – the diagonal - that revives, “transfigures” the operations materialized

at Wagner by the melody “without end”.

And here is an example.

Fourth movement (exposition :

transition between the two themes)

![]()

Far away,

we can see that the twist of voice results of quartet’s meshes

(see the

big notes in this example) :

I let you try to eventually recognize it during

the concert of this evening.

I will break now in this stage, waiting for the

concert this evening.

–––––––